Colonel Francis Charles Burton

1885-1931

For a change, I am writing about someone whose name is connected to a grave in Ireland, but who is not himself buried here.

The grave is that of the artist, Sir Frederick William Burton, Director of the National Gallery of England, whose painting ‘The Meeting on the Turret Stairs’ was voted Ireland’s favourite painting.

I have timed this biography to coincide with the National Gallery’s retrospective on Sir Frederick, which will run from October 2017 until January 2018.

This article is about Sir Frederick’s nephew, Francis Charles Burton, in which all the leading ladies seem to be called Isabella.

Sir Frederick’s younger brother, Rev Robert Nathaniel Burton, was vicar of Clonagoose in County Carlow during the Great Hunger. He was also Chaplain to the artist and antiquarian, Lady Harriet Kavanagh. (Her Egyptian collection can be seen in the National Museum of Ireland.) As famine and disease raged through the country, Rev Burton often gave his breakfast to the starving and the last rites to the dying – even to Roman Catholics in the absence of their own priest. Sadly, the good reverend succumbed to one of the diseases in the Grim Reaper’s taskforce – typhus, smallpox, famine fever, Asian cholera . . . And as though this was not bad enough, he died on Christmas Eve of 1850. His widow, Isabella, was left to rear her hungry children, the youngest only three years old. To her relief, brother-in-law Frederick William stepped in and offered financial assistance with the raising of his nephews and nieces.

The eldest of Rev Robert’s children was Charles Francis Burton, born in 1845. Young Burton enlisted with the 38th (1st Staffordshire) Regiment of Foot and went to India in 1866. Three years later, upon admission to the Staff Corps, he was promoted to Captain and joined 1st Bengal Lancers, more popularly known as Skinner’s Horse.

The young captain led a Punjab battalion – the 2,000 strong Kapurthala Contingent, to be exact – in the 1st campaign of the 2nd Afghan War of 1878-1880. Later, as Political Officer in various parts of Afghanistan, Burton raised native levies to swell the government’s coffers. During operations in 1879, he managed to recover 21 bags of looted mail, which was gratefully acknowledged by the celebrated General Frederick Roberts, Commander of the Kabul Field Force. Burton went on to win the Viceroy’s admiration when he acted as Political Officer and Guide to Colonel McKenzie’s forces during the capture of Badda. Upon the withdrawal from Kabul, Burton took charge of the rear guard.

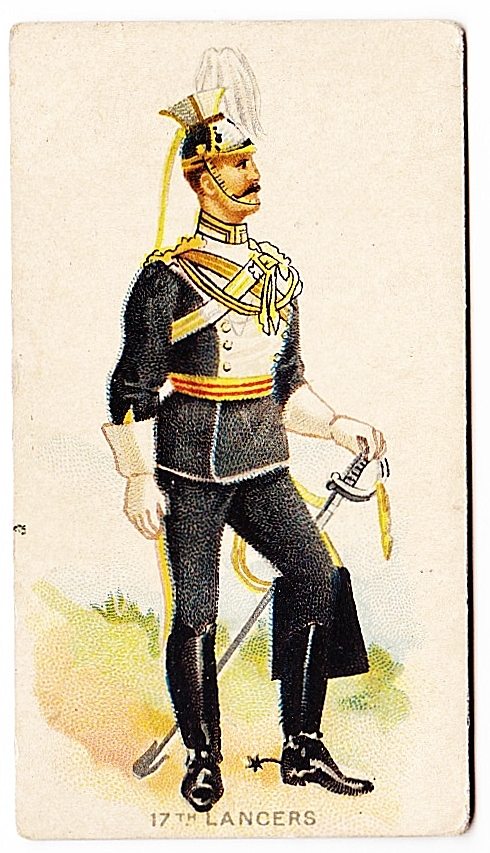

For a brief period in 1891, Burton was Second-in-Command, Staff Corps, before taking over as Officiating Commander of 17th Bengal Cavalry. Costume changes must have been expensive, moving from the yellow uniforms of the 1st to the blue of the 17th.

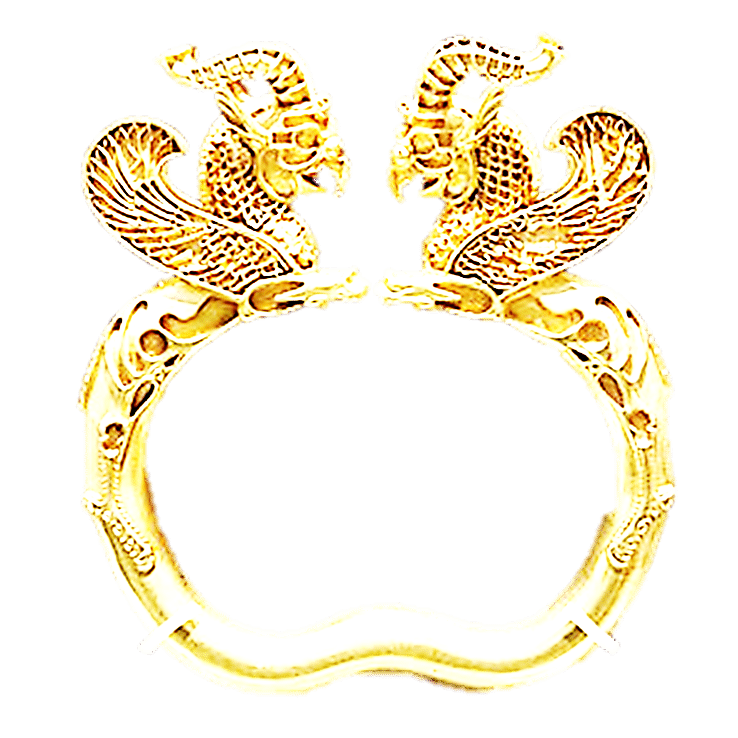

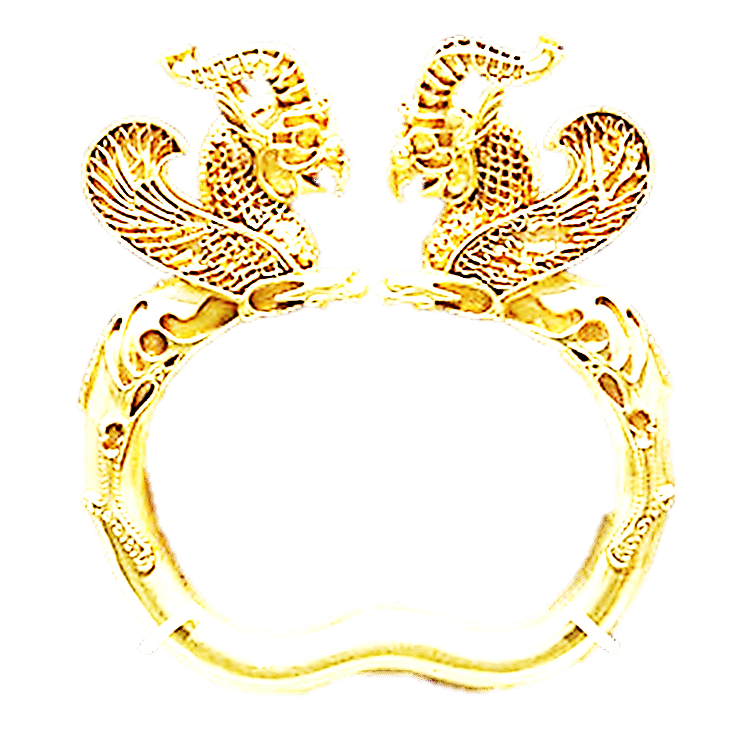

As Political Officer of the Khurd Kabul area in Ghilzai district he was doing his best to keep the lines of communication open between the government and the Afghans when a particularly interesting snippet of information came his way. Three Kokhand merchants had been ambushed by Ghilzai bandits on the caravan route between India and China and held hostage in a cave on the Kabul-Peshawar road. Nothing unusual about that except . . . the captured treasure sounded very interesting, indeed. Burton leapt on his horse and, along with two orderlies, galloped to the hills where he found the Afghan tribesmen killing each other over the loot. The nearby cave was practically illuminated by the treasure spread on the floor – 80,000 rupees worth of gold! Perhaps Burton did not realise that this was the legendary Oxus Treasure because he restored some of it to the merchants. They are believed to have sold him a gold lion-and-griffin-headed bracelet but I think it more likely that he was given the piece as a token of gratitude by the foxy merchants who knew they had got off lightly.

While Burton was kept busy on the North West Frontier, his Irish-born wife, Isabella, was enjoying the life of a memsahib in the summer capital of Simla. It was on her scintillating character that Rudyard Kipling, a friend of the couple, based his well-known character, Mrs Hauksbee. The unique yellow uniforms of Skinner’s Horse were reflected in the livery of Mrs Hauksbee’s rickshaw wallahs. Kipling was obviously smitten by her as Mrs Hauksbee appears in eight of his stories on India ‘Plain Tales from the Hills’. Mrs Burton is also thought to be ‘The wittiest woman in India’ to whom the book is dedicated, although Kipling’s mother claimed the title, too.

Burton’s last posting, until 1897, was Commanding Officer of the 2nd Lancers (Gardner’s Horse) the most highly-decorated regiment of the Indian Army.

Colonel Charles Francis Burton retired in 1901 and settled in Tunbridge Wells. He never married and died in 1931 at the relatively young age of 46.

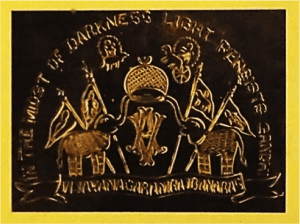

1st Bengal Lancers

1st Bengal Lancers started life in 1803, as an irregular cavalry regiment raised to protect the trade interests of The East India Company. It was named 1st Skinner’s Horse, having been raised by James Skinner, the son of a Scottish Colonel and Rajput princess. A popular officer affectionately known as ‘Sikander Sahib’ by his men, Skinner went on to raise two more cavalry regiments. Later, the 2nd and 3rd were amalgamated to become 1st Duke of York’s Own Lancers (Skinner’s Horse).

Apart from the three Afghan wars, the 1st Bengal Lancers saw action in WW1 as well as the Boxer Rebellion in China.

Today, Bengal Lancers is a senior cavalry regiment and the name continues to enthral . . . as confirmed by Fuller’s full-bodied and spicy pale ale ‘Bengal Lancer’.

Burton’s uncle Fred, who had raised Burton and his siblings, had died in 1900 and the elaborate tombstone in Mount Jerome Cemetery was erected by his grateful nephews and nieces, all except Isabella.

The flame-haired Isabella Julia Burton, married a solicitor called Frederick Gifford and had 12 children. Of their six daughters, two married signatories of the Proclamation of the Irish Republic during the 1916 Rising. One of the girls, Grace Gifford, famously married Joseph Plunkett in the chapel of Kilmainham gaol before he was executed.

Burton’s other sisters, Hannah, Emily and Mary, never married and went into nursing. One of his brothers, Alfred, took holy orders and another, Henry Bindon, was a senior partner in HB Burton Solicitors in Dame Street, Dublin. He lived in Leeson Street and enjoyed penning poems as a diversion from lawyers’ briefs. He is buried in Mt Jerome along with his wife, Fanny Elizabeth. However, in more than one list of siblings, Fanny Elizabeth appears as his sister.

I give up!

Oxus Treasure

Between 1877 and 1880 a hoard of gold and silver was unearthed by the River Oxus (or Amu Darya) which flowed past Afghanistan. The find included jewellery, plaques, ornaments, coins and idols thought to be from the Achaemenid Persian period. It is understood the discovery was made in an ancient fort by people of the Bokhara region, part of the Persian Empire. The finders sold the hoard to Indian merchants – the bulk to the three men rescued by Burton. After their treasure was restored, the men sold the precious objects to dealers in the market in Rawalpindi from whom many items were bought by British General and archaeologist, Sir Alexander Cunningham. Later, Cunningham’s collection was acquired by Augustus Wollaston Franks, museum administrator and leading authority on mediaeval antiquities. Precious stones had been gouged out from many of the articles. Upon Franks’ death in 1897, all his Oxus collection was bequeathed to the British Museum. The acquisition is unusual inasmuch as it was not the result of colonial plunder.

Burton sold his bracelet to the Victoria & Albert Museum in 1884 for £1,000.