L/ Corporal John Flannery – 1885 – 1961

John Flannery’s burial was recorded in Deansgrange Cemetery register but I could not find his grave. With the help of cemetery personnel, I discovered he was buried in the plot of the Dockrell family. If his name was not inscribed on the tombstone, it could be for a very good reason. John Flannery was born in Tipperary to Patrick and Mary Annie (nee Egan) in 1885. His father was a labourer and he had at least four siblings. His father died when Flannery was eighteen and his mother married Michael Mangan in 1910.

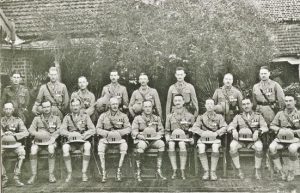

Meanwhile, Flannery went along to Brunswick Street in Dublin and joined the Connaught Rangers in 1908 for a ten-year period. He was assigned to the 1st Battalion which embarked for India and was quartered in Ferozpore, Punjab. Upon the outbreak of war in 1914, the 1st Battalion was sent to France where it fought alongside the 2nd Battalion. Private Flannery was wounded in Flanders and I’m not sure if he had re-joined his battalion when it embarked for service in Palestine, Mesopotamia and Turkey the following year.

When the war ended, the Rangers returned to their depot in Dover, Kent. By now, Flannery’s ten-year period of service was over. He re-enlisted and, once again, sailed to India with the 1st Battalion in October 1919.

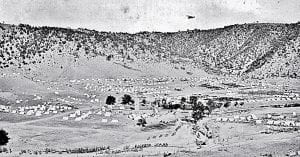

Life in Wellington Barracks in Jullunder and, further north, in cool Solon, both in Punjab, was tickety-boo until rumours began to filter through about the brutality of British authorities against the republican movement in Ireland. Completely missing the irony of their own role in the British army in India, the Rangers decided to protest . . . by calling for a mutiny. All the better if they could win local support by drawing parallels between the Irish situation and the Indian.

Life in Wellington Barracks in Jullunder and, further north, in cool Solon, both in Punjab, was tickety-boo until rumours began to filter through about the brutality of British authorities against the republican movement in Ireland. Completely missing the irony of their own role in the British army in India, the Rangers decided to protest . . . by calling for a mutiny. All the better if they could win local support by drawing parallels between the Irish situation and the Indian.

Lance Corporal Flannery’s part was undoubtedly active – he even cadged green, white and ‘gold’ fabric from sympathetic market-traders to make rosettes for the mutineers. The mutiny lasted just three days but at the ensuing trial, he claimed to have merely acted as a calming influence on the angry troops and a liaison between them and their British officers. Reams of conflicting reports have been written about the mutiny but there is an unanimous agreement that Flannery tried to ‘lighten his own sentence at the expense of his comrades’. Branded ‘turncoat’, ‘traitor’ and ‘informer’, Flannery was court-martialled but his death sentence was commuted to penal servitude for life. The 1st Battalion was sent to Rawalpindi and Flannery was sent to Parkhurst prison on the Isle of Wight and later, Wandsworth in London. Luckily for him, the creation of the Irish Free State reduced his sentence to two years and four months.

He returned to Ireland with a hernia to accompany his stigma. Perhaps in order to redeem himself, Flannery dedicated his retirement to campaigning for his fellow-mutineers’ pensions to equate that of veterans of the Irish War of Independence. The Connaught Rangers (Pension) Act was passed in 1936.

In January 1934, Flannery married Catherine, daughter of John Dockrell, painter, in St Joseph’s Church, Glasthule, in the Rathdown district of Dublin. She was obviously not his first love as he already had clasped hands and ‘true love’ tattooed on his left forearm. However, he had nine years with his wife before she died of cancer in 1947. Although her name appears as Kathleen in the marriage certificate, it is Catherine on the family grave so I assume it is the correct name. She was buried with her mother who had died in 1938.

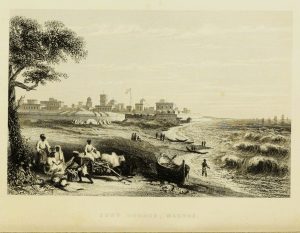

Flannery found employment as a messenger in the Land Registry Department of the Four Courts. Almost thirty years later, he decided to record events of the Connaught Rangers mutiny – as he remembered them. In the self-aggrandising report, he refers to himself as ‘the leader’. For me, the most interesting passages were his delightful description of a native Indian bazaar. Rather amusingly, he claims that the Officer Commanding told him, ‘. . . it is a General you were intended for’. I would rephrase that to ‘. . . it is a Kipling you were intended for’.

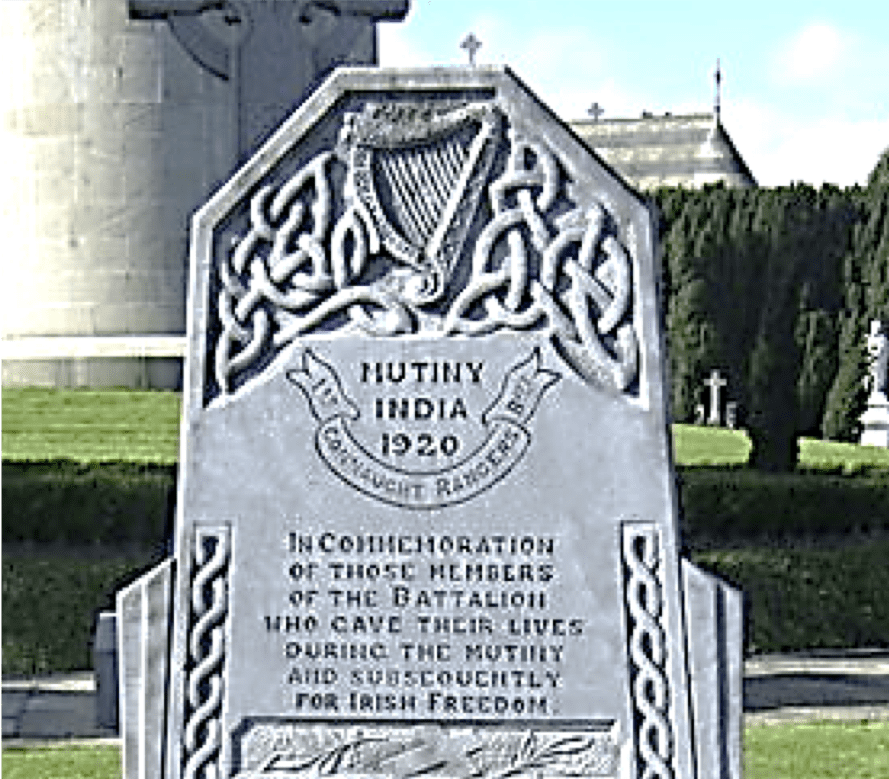

In later years, Flannery moved from Glasthule Road to Thomas Street to live with his niece Anastatia (or Anastasia) O’Reilly, daughter of his brother, Thomas. On the 29th of June 1961, he was taken to St Kevin’s Hospital (now St James’) where he died of hepatic failure the next day. He was buried with his wife in the Dockrell family grave. His name does not appear on the tombstone nor is it to be seen on the Connaught Rangers’ Mutiny memorial in Glasnevin Cemetery, Dublin.

I recently met a man who had been in India in the 1960s and was very proud that New Delhi’s central hub, Connaught Circus or Connaught Place, was named in gratitude for the Connaught Rangers’ mutiny in support of the Indian National Movement. I had to burst his bubble by telling him it was actually named after the Duke of Connaught and the Rangers’ mutiny had nothing to do with the Indian freedom struggle. The confusion between the two Connaughts is not likely to resurface since the Delhi district was renamed Indira Gandhi Chowk.