Major John Langran Giddings

1818-1873

John Langran Giddings’ grave confirms ‘His end was peace’. Of course it was, given the seaside tranquillity of Sandycove, County Dublin, after the ferocity of India.

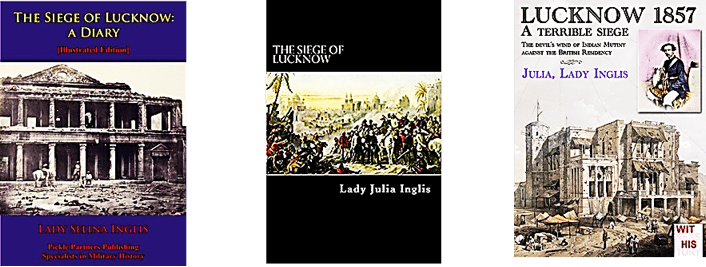

It was infuriating that there was no mention of his Indian connection on his tombstone – I had to find that out for myself. I recalled a Giddings being mentioned in The Honourable Lady Inglis’ diary of the Lucknow mutiny so maybe . . .

Yes! This was Lady Inglis’ Giddings! Buried in Deansgrange!

Giddings was born in Yorkshire and by a clever deduction from his tombstone, I was able to work out that he was born around 1818. I tried searching his roots via his brother, but he merely appears as W Giddings, builder, Norwood. In fact Giddings’ middle name of Langran proved quite a mystery, too, as he usually went by the title of John L Giddings.

Giddings joined the 32nd (Cornwall) Regiment of Foot in 1835. His first encounter with obstreperous colonies was in 1840 when his regiment found itself sorting out clashes between the Francophiles and Anglophiles of Lower Canada. When the movers and shakers of Westminster sent Lord Durham to Canada, it was a wise choice. The new Governor recommended the unification of Upper and Lower Canada. And that was it.

In the ensuing lull, some of the young soldiers’ ‘fancy lightly turned to thoughts of love’, as Alfred, Lord Tennyson, was saying at the time. Giddings married Margaret Barry in Toronto in 1940 just 10 days after Colour sergeant John Mahon married Mary Anne Powell. I imagine both brides were Canadian.

The excitement having died down in Canada, the regiment was shipped back to England in 1841. After four years the 32nd sailed for India.

It looks like young Giddings misplaced his wife sometime in the intervening years because in April 1847 he married Maryanne Mahon, ex-wife of Colour Sergeant John Mahon.

Upon arrival in India, the regiment marched straight to Punjab where the Anglo-Sikh wars raged. Giddings appears as Quarter Master in 1848.

Starting with the Siege of Multan and ending with the Battle of Goojrat (Gujarat), the Sikh wars kept the 32nd on its blistered toes. If only they had known what a waste of energy it was – the infighting, betrayals and factions within the Sikh camps would have handed Punjab to them on the Maharani’s silver platter. In the end, a Pyrrhic victory served up the young heir to Punjab’s throne on a golden platter and Crown Prince Duleep Singh was whisked off to Queen Vic (the empress, not the pub). After all, Her Maj was already in possession of his large diamond, the Kohinoor, so why not have the prince as well?

Giddings collected his Punjab Medal, complete with clasps for two Anglo-Sikh campaigns, and in November 1856 donned the bicorn hat (sans cockade) of Paymaster.

Meanwhile, ugly rumblings of a mutiny were growing louder in Lucknow. After those savage natives had done away with the popular Commissioner, Sir Henry Lawrence, the defence of the Residency was taken over by Lt Col Inglis of the 32nd. During the siege, Giddings stepped in as Adjutant, as the permanent Adjutant was on leave and his replacement killed by the rebels. (His wife’s first husband, John Mahon, was also present in Lucknow.) In her famous personal account of the siege of Lucknow, the Hon Lady Inglis was suitably impressed by her husband’s regiment, referring to them as ‘the gallant band of the twenty 32nd men like the steel head of the lance to pierce the way . . .’. She noted that in case of a disturbance, all occupants of the Residency were to assemble in the Giddings’ house. Mary Anne Giddings was of enormous help to Lady Inglis during the siege of the Residency.

I know the Residency well, having picnicked in the grounds of the ruins when I was a child. The guides relate the legend of Jessie’s dream. Huddled in the cellar with terrified women and children, Jessie kept their hopes alive by claiming she could hear horses’ hooves when she laid her ear to the floor – Sir Colin Campbell was surely on his way to rescue them. Alas! Campbell arrived too late to save most of the women and children.

Had Irishman Thomas Henry Kavanagh not blackened his face and stepped out during the night ‘with the devotion of an ancient Roman’ to guide Sir Colin Campbell’s army ‘through a city thronged with merciless enemies’, Giddings would have joined the bodies in the Residency cellar. In Christ Church, Lucknow, built as a memorial to the Mutiny (and where I was confirmed), a marble plaque records Kavanagh’s heroism in dramatic terms.

The 32nd Cornwall won 4 Victoria Crosses for its defence of the city and Giddings got his Indian Mutiny Medal, complete with clasp. Then he rushed off to assist in the relief of Cawnpore (Kanpur), and claim another clasp.

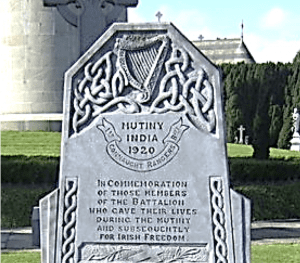

A memorial at the Residency in Lucknow commemorates ‘the gallant part taken by H.M. 32nd Foot in the heroic defence of The Residency in 1857 also to the memory of the Officers, Non-commissioned officers, men, women and children of the Regiment who perished here and at Cawnpore’.

Giddings attained the rank of Hon Captain in late 1861. He drew up a full list of all the casualties of the relief of Lucknow – which, some 160 years later, being ‘excessively scarce’, was flogged on the internet for £600.

In the summer of 1865, he retired on half pay with the honorary rank of Major and settled in Ireland.

John Langran Giddings died in 4 Breffni Terrace, Sandycove, in 1873. The upmarket property still stands but, some years ago, featured in a court case over parking in the laneway behind the house.

Giddings’ obituary appears in The South Australia Advertiser, placed by his brother, W Giddings. The newspaper records his death as occurring of ‘acute heart disease brought on by Gam’. Googling Gam revealed it as Global Asset Management, but I think Giddings’ death was more to do with his leg.

Old soldiers don’t die – they just lay down their arms . . . or legs.

The Daughters

Sorting out the Giddings’ girls was not easy due to the conflicting information on the internet. After much cross-checking and sorting of dates, I have come to this conclusion . . .

Mary Anne Mahon already had a daughter, christened . . . Mary Anne! She was born in 1846, a year before Giddings married her mother. I am not sure whether she was John Mahon’s daughter, or Giddings’. In her early thirties, she emigrated to Australia. After attempts as governess and dance teacher, she married a dodgy character called Arthur Constant Aucher, an ex-con who dabbled in various businesses. They had three children – two boys and a girl. Maryanne died in 1899 and Aucher lost no time in marrying again.

Then there was Emily, who was born in 1848, during the Sikh wars. I found nothing more on her.

Yet another Mary Anne Giddings appears in the 1901 census of Ireland, married and living in Breffni Terrace. She was 40 years old at the time and I think this was a third daughter. She was living with her 20-year-old daughter, Elizabeth Giddings, born in London, Canada – quite possible, assuming her grandmother was Canadian. (It seems strange that Elizabeth bears the surname Giddings – unless her mother married a man of the same name.)

I came across references to one of the daughters being 7 years old during the Lucknow Mutiny. But, according to my calculations, the older girls would have been 11 and 9, and younger one yet to be born.