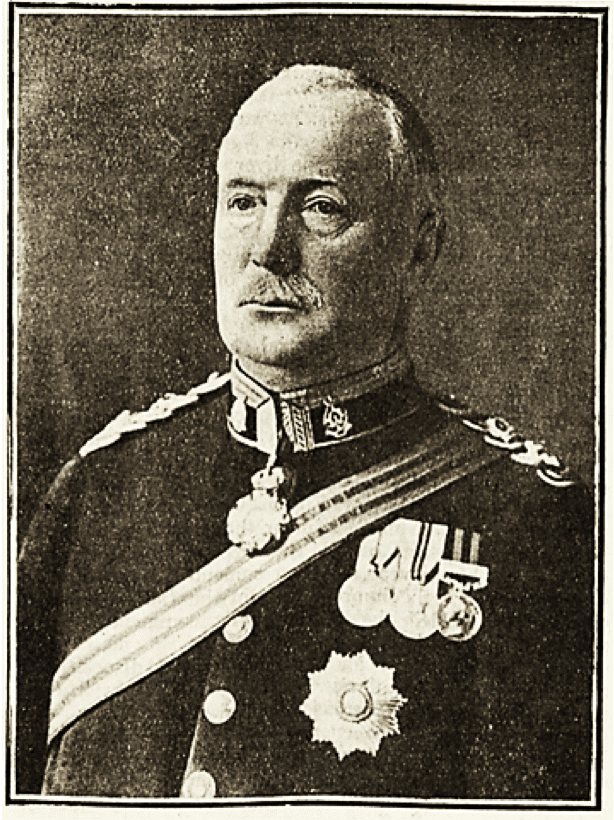

LT COL SIR WALTER JAMES THOMPSON BUCHANAN K.C.I.E

1861-1924

Walter Buchanan was the eldest of Robert and Mary Buchanan’s eight children. Robert, like his father before him, was Coroner of Fintona, County Tyrone. Walter James Thompson Buchanan as born in Londonderry on 12 November 1861 and was educated in Foyle College.

He went on to study medicine in Trinity College, Dublin, and took a further qualification in Vienna before becoming Resident Surgeon in Sir Patrick Dun’s Hospital as well as the National Eye and Ear Hospital, both in Dublin.

In 1887 he entered the Indian Medical Service as surgeon in the Bengal Presidency. Almost immediately, he was hurled into three successive expeditions – starting with Hazara.

Hazara Expedition 1888.

The Hazara Expedition or Black Mountain campaign of 1888 was waged during the ongoing war on the Northwest Frontier of India, between British troops and Afghan tribesmen. It was assembled in response to the killing of two British Officers and four Gurkha soldiers but lasted just six weeks.

Seven-pounder guns were dismantled and carried on mules by the Indian Mountain Batteries. Villages on both sides of the River Indus were destroyed before a deputation of tribal elders (known as Jirga) negotiated a peace treaty involving a fine of 1,500 rupees and the surrender of five headmen as hostages. The beautifully-fertile Hazara region is now in Pakistan. Still breathless from Haraza, Walter Buchanan marched straight into Chin-Lushai.

Chin-Lishai Expidition 1889

The fracas on the Burmese border began in 1871 when fierce guerrilla tribes raided Assam and captured British subjects, including six-year-old Mary Winchester. The prisoners were freed (although, by all accounts, little Mary was reluctant to go home) and peace was restored. In 1889 trouble flared up again. The three-pronged Chin-Lushai Expedition was organised to punish the tribes. And punish them they did. By the Chief Commissioner of Chittagong’s own admission, the ferocious subjugation of the area left whole villages with widows. The short campaign subdued the tribes . . . until the British tried to coerce the tribesmen into working for them as coolies or labourers.

Once again, Buchanan had little time to pack his stethoscope before hurrying on to Manipur in 1891.

Maniour Field Force 1891

Manipur was a little independent kingdom in east India that had never been colonised but its strategic location between India and China kept it in British sights. Repeated invasions by Burmese forces and constant internal battles between the king’s heirs gave the British the perfect opportunity. James Wallace Quinton, Chief Commissioner of the neighbouring state of Assam, was sent to Manipur to remove the Pretender to the throne and recognise the Regent. However, believing the true motive to be the expansion of the Empire, an infuriated crowd of rebellious Manipuris beheaded Quinton and four accompanying officers.

The Manipur Field Force set out on the army’s third revenge campaign. The State was brought under control and quickly added to Britain’s territory in India.

(James Wallace Quinton is remembered on the family grave in Deansgrange Cemetery, Dublin.)

Returning to civil employment in 1892, Buchanan joined the Jail Department in the province of Bengal, serving first as Superintendent of Bhagalpur Central Jail and later, Alipur Central Jail in Calcutta. Here, he married Edith Lilian Bryne in 1891. She was the daughter of Edward Simpson Byrne, Deputy Auditor General in Calcutta, who was born in Calcutta. Five of his six children were born in four different Indian cities – Edith Lilian in Hyderabad (now in Andhra Pradesh) in 1870. Two years after her marriage, Edith had her first and only child in Exeter, Devon, named Maurice Bevor (sometimes, Beaver).

In 1902 Buchanan was appointed Inspector General of Jails in the same province. During his administration of Bengal jails, the death rate dropped because sanitation was improved.

An authority on tropical diseases and medicine, Buchanan wrote several books including ‘The Darwinism of To-day’ in 1891 and ‘The Jail Manual’ in 1898. He contributed articles to various journals, such as ‘Quain’s Dictionary of Medicine’ and ‘Taylor’s Medical Jurisprudence’. For the last twenty years of his career, he edited The Indian Medical Gazette – the longest surviving medical journal in India.

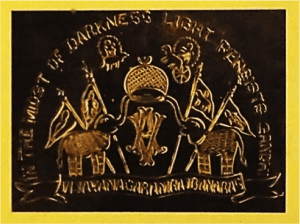

Medicine was not Buchanan’s only passion. His wide knowledge of Northern Bengal resulted in the publishing of his first book on travel ‘Tours in Darjeeling and Sikkim’. Freemasonry was another of his interests.

In 1913, Buchanan was appointed Companion of the Indian Empire. Two years later, he was promoted to Knight Grand Commander of the Order of the Indian Empire. But sandwiched between the honours was tragedy – both his mother and wife died in 1916. I’m not sure where Lilian died.

As a Member of the newly-formed Indian Prisons Commission, Buchanan set out in 1919 on a mission to study the prison systems of other countries with a view to applying them to India. He served on the Indian Jails Committee which visited the Andaman Islands and recommended the abolition of its penal settlement by 1921. However, some political prisoners were still sent there for the next ten years. (I have described the island’s cellular jail in the biography of John George Collis.)

Buchanan retired in 1919 and reluctantly left India to return to Ireland where, for the next three years, he served as a member of the Central Council of the British Medical Association on its Naval and Military Committees. He established the Walter Buchanan Scholarship at Epsom College in Surrey (for poor members of the medical profession) with the proviso that preference be given to the sons of Indian Medical Service officers.

Sir Walter James Buchanan died of pneumonia at the age of sixty-two in 1924. His unmarried sister, Emily, died in 1933 and is buried with him.

Colonel Maurice Bevor Buchanan T.D.

1893-1965

Lt Col Walter James Buchanan’s only son, Maurice Bevor, was born in Exeter in 1893. He became an officer in The Royal Scots Fusiliers. The young Captain was wounded near Ypres in 1914. Just six months later, he returned to the battlefield sporting his Wound Strip, was twice mentioned in despatches and won the Mons Star.

Lt Col Walter James Buchanan’s only son, Maurice Bevor, was born in Exeter in 1893. He became an officer in The Royal Scots Fusiliers. The young Captain was wounded near Ypres in 1914. Just six months later, he returned to the battlefield sporting his Wound Strip, was twice mentioned in despatches and won the Mons Star.

Maurice married Charlotte Aimée Walker in Yorkshire in June 1925. Charlotte’s father was Frederick Edmund Walker, county magistrate, of Ravensthorpe Manor near Thirsk and the society wedding was conducted by the groom’s uncle, Rev Canon L G Buchanan.

Upon retirement, Maurice was placed on the Active List and assumed Territorial Forces duties. As Deputy Lieutenant of the County, he was awarded the Territorial Decoration. In 1954 his tenure as Hon Colonel of a TA unit expired and he settled down to a quiet life in Hull Lodge, Ayr, Scotland. In 1963 he was awarded the OBE for political and public services in Ayr.

Colonel Maurice Buchanan TD, died in 1965 at the age of seventy-one. I could not find where his widow died and the couple appear to have had no children.

The Buchanan Family of Londonderry

The Buchanans of Londonderry gave more sons to the army. Lt Col Walter James’ brother, Robert Eccles, was an architect and civil engineer. Of his three children, two joined the army. Older son, Edgar James Bernard, was an officer in Indian Expeditionary Force. He saw action in Egypt with Queen’s Own Sappers and Miners and rose to the rank of Brigadier, serving in the War Office during WWII.

Younger son, 2nd Lieutenant Richard Brendan was completing his medical studies when he was gazetted to the Royal Army Medical Corps. However, he was denied active service until fully qualified, so he transferred to The Royal Scots Fusiliers. He was in the army a mere ten months before meeting his end in the trenches of Gallipoli. He was only twenty-one and is buried in the Lancashire Landing Cemetery there. However, his hometown did not forget him – his name is inscribed on the Diamond War Memorial in Londonderry.